I hope you all are staying safe and healthy. Especially if you are in the path of the hurricane in the gulf or the wildfires in California, you are in my thoughts. And if you are out marching for justice, please stay safe. Sending love. ♥

This is Part 5 of a thirteen-part braided essay celebrating my passion for music, intertwined with travel and spirituality. I will post one section every few days until it is all here. If you haven’t read the earlier sections, please start there: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4.

Marked with Musical Notes – Part 5

Bosnia: Mostar

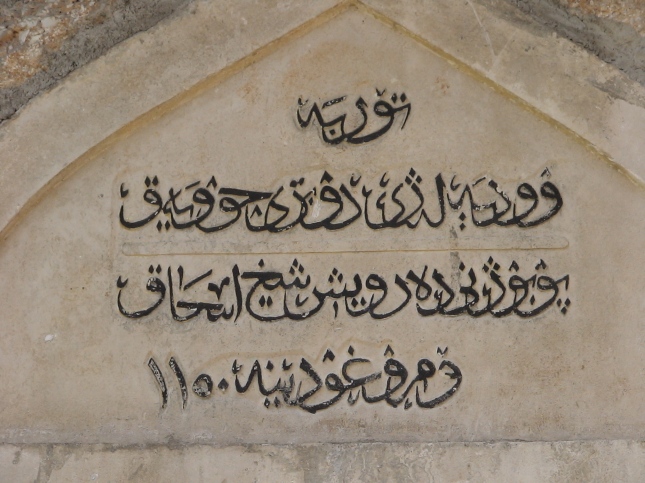

I squint at the engraving on the mausoleum outside the Koski Mehmed Pasha Mosque. The text is written in the Arabic alphabet, but the language is Bosnian. This script-language mix is called Arebica and was used when Bosnia was part of the Ottoman Empire. Now, Bosnians write their street signs in the Latin and Cyrillic alphabets. The letters above the mausoleum door intertwine like tree branches in the grey stone, and I can only make out a few words: turbe (mausoleum) and the title and name “Dervish Shaykh Ishaq.”

Behind me, a woman fills her bottle from a spout on the stone-roofed fountain. Closer to the Adriatic Sea, Mostar is hotter than Sarajevo and the fresh, cool water, available to everyone, is most appreciated. Next to the fountain stand weather-worn tombstones, some with round turbans carved onto them, indicating buried dervishes. The dead are never far. Flashes of hot pink, orange, and red billow behind the tombstones, next to the mausoleum, where the souvenir shop sells pictures, tapestries, and clothing, including belly-dancing costumes, evidently for tourists who assume that every country with Muslims also has belly dancers.

I glance at my watch and knock at an office door. Singer Zejd Šoto greets me and invites me inside for the interview. Zejd has short, brown hair and bright blue eyes. He started playing the accordion at the age of four—his family wanted to instill an interest in sevdalinka and folk music over rock—and began singing with Hor (Choir) Sejfullah as a young teen. With the other boys in the choir, he performed for army events during the Bosnian War. He now performs spiritual music, mostly as a soloist, in several languages including English, Bosnian, Arabic, and Turkish.

Zejd answers his phone and tells the caller he is busy. I smother a laugh when he refers to me as a novinarka—a journalist.

After the interview, I walk back outside, into the verve of the country’s fifth-largest city and the cultural capital of the region of Herzegovina. Mostar teems with Ottoman, Austro-Hungarian, and communist-era architecture: mosques and churches, monuments and, most notably, bridges.

The Stari Most (Old Bridge) is Mostar’s most recognizable landmark. It was originally designed by an apprentice of the famous architect Mimar Sinan and opened in 1566. Carved from pale grey limestone called tenelija from a local quarry, the arch spans the emerald green Neretva River, one of the cleanest—and coldest—rivers in Europe. The keepers of the bridge were called mostari, and that’s how the city got its name. The Stari Most was destroyed in the recent war and rebuilt in 2004.

I look up as a diver plummets from the center of the bridge and hits the water amid applause. A second speedo-clad diver climbs the steps of the bridge in the wake of dispersing tourists. He steps onto the ledge and beckons with his hands to gather an audience. He bends his knees and looks down at the water, then straightens, turns, and beckons again. People pass without stopping, and he descends from the ledge and pulls on his clothes.

The tense, vibrato voice of Šaban Bajramović floats from a nearby music store, accompanied by the melody of Mišo Petrović’s guitar. The band is Mostar Sevdah Reunion, and they play a blend of jazz, contemporary music, and sevdalinka, an emotional urban folk genre. Šaban Bajramović is not a member of the band, but they have recorded two albums with the prolific Serbian-Roma singer. Roma in Europe suffer discrimination and abuse, but Balkan Roma musicians are prized. Bajramović, the King of Roma music, composed over 650 pieces of music but died in poverty in 2008 at the age of seventy-two.

Music unites people here, as illustrated in Ruth Waterman’s book When Swan Lake Comes to Sarajevo. Throughout this true account of her role as guest conductor of the Mostar Sinfonietta, Waterman uses the Stari Most as a symbol of the relations between the various ethnic and cultural communities in the region and presents music as a bridge as well.

Rock critic Anke Perković refers to music as Yugoslavia’s Seventh Republic because of the role it played in integrating the different communities of the former country. Music cannot completely heal the wounds left by the war that followed the breakup of Yugoslavia. But, like the reconstructed stone bridge of Mostar, it brings people together who wish to hear and connect.

Continue to Part 6.

Above image by Annalise Batista from Pixabay

Images below are mine from Mostar, 2009.